1. The Concept: What is a Biodiversity Hotspot?

A Biodiversity Hotspot is a biogeographic region that is both a significant reservoir of biodiversity and is under severe threat from human activity. The concept was first introduced by the British ecologist Norman Myers in 1988 and has since been refined and adopted by Conservation International as a cornerstone global conservation strategy.

The core idea is powerful yet simple: in a world with limited conservation resources, we must prioritize our efforts. Hotspots act as a strategic blueprint, identifying the areas where the greatest number of unique species face the most immediate risk of extinction. Protecting these areas would safeguard a massive proportion of the world’s terrestrial biodiversity relative to the land area covered.

To be officially designated as a Biodiversity Hotspot, a region must meet two strict, quantitative criteria:

- High Species Endemism: It must contain at least 1,500 species of vascular plants as endemics. This means these plants are found nowhere else on Earth. This criterion highlights the region’s uniqueness and irreplaceability.

- Significant Habitat Loss: It must have lost at least 70% of its original primary vegetation. This criterion highlights the urgency and the severe threat the region’s native species are under.

In essence, a hotspot is a place of both extraordinary biological wealth and a conservation crisis.

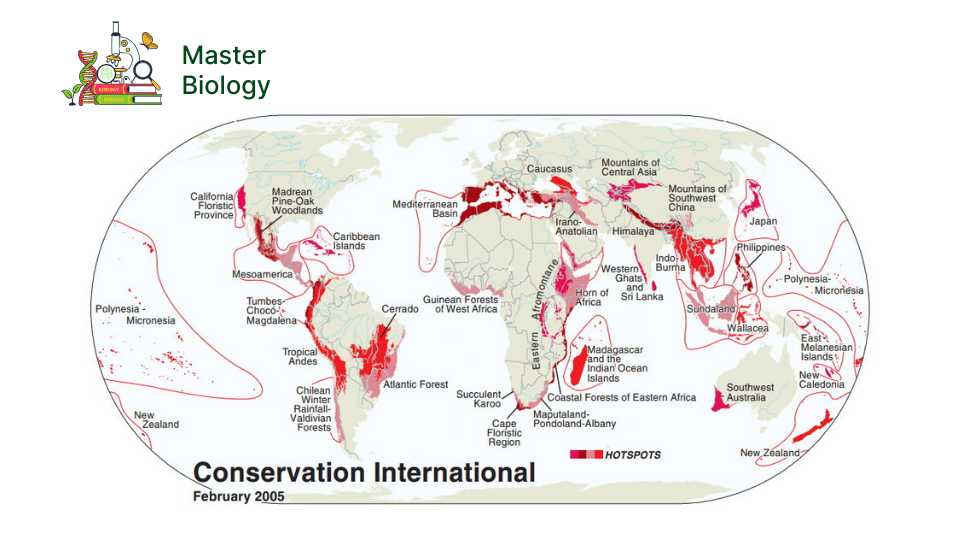

2. Global Patterns: Where are the Hotspots Located?

There are currently 36 recognized biodiversity hotspots around the world. Together, these hotspots cover only about 2.5% of the Earth’s land surface. Yet, astoundingly, they are the exclusive home for 43% of the world’s endemic plant species, 35% of endemic land vertebrate species (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians), and countless invertebrates.

The distribution of these hotspots is not random. They are primarily found in tropical and subtropical regions, often in mountainous or coastal areas with complex geography that promotes speciation (the formation of new species). However, they also include unique Mediterranean-type ecosystems.

Prominent Examples of Biodiversity Hotspots:

- The Tropical Andes (South America): The most biodiverse hotspot, containing about one-sixth of all plant life on Earth in less than 1% of its land area. It is home to thousands of endemic species, like the spectacled bear and countless orchid species.

- Sundaland (Southeast Asia): Includes islands like Borneo and Sumatra. It is famous for its incredible rainforests and iconic species found nowhere else, such as the Orangutan, the Sumatran Tiger, and the Rafflesia (the world’s largest flower).

- Indo-Burma (Southeast Asia): Encompassing the Mekong River region, this hotspot is a cradle of freshwater biodiversity, with a staggering number of endemic fish, turtle, and bird species being discovered regularly.

- The Mediterranean Basin (Europe, Africa, Asia): While not as lush as a rainforest, this hotspot has exceptionally high plant endemism, with over 11,000 endemic plant species, including the ancient olive and cork oak trees.

- The Cape Floristic Region (South Africa): A relatively small area that is home to the world’s most extraordinary concentration of non-tropical plant life, the Fynbos. Nearly 70% of its 9,000 plant species are endemic, including the iconic Proteas.

- The Western Ghats and Sri Lanka (India): These ancient mountain ranges are a evolutionary hotspot, sheltering a vast number of endemic amphibians, reptiles, and fish, like the Malabar pit viper and the Lion-tailed macaque.

- Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands: Isolated for millions of years, Madagascar alone is home to 5% of the world’s plant and animal species, including entire families like the lemurs (over 100 species) and the bizarre-looking baobab trees.

3. The Critical Importance and Threats: Why Do Hotspots Matter?

The importance of Biodiversity Hotspots is immense and multifaceted, but their existence is precarious.

A. Importance:

- Arks of Irreplaceable Biodiversity: They are the last refuges for a massive proportion of Earth’s unique life forms. Losing a hotspot means losing thousands of species forever.

- Ecosystem Service Providers: These regions provide vital services to humanity, including water purification (cloud forests), climate regulation (carbon sequestration in forests), pollination for agriculture, and protection from natural disasters like floods and cyclones (coastal mangroves and forests).

- Sources of Scientific Discovery: Hotspots are living laboratories of evolution. They are untapped reservoirs of genetic information that could lead to new medicines, agricultural crops, and industrial materials. Many potential cures for diseases are lost when a species goes extinct in these regions.

- Cultural and Aesthetic Value: Many hotspots are homelands to indigenous and local communities whose cultures, traditions, and livelihoods are intimately linked to the native biodiversity.

B. Primary Threats:

The very reason these areas are “hotspots” is the severity of the threats they face.

- Habitat Loss and Fragmentation: This is the single biggest driver. The 70% habitat loss criterion is primarily due to deforestation for agriculture (e.g., palm oil, soy, cattle ranching), logging, and urban sprawl. Remaining habitats are often broken into small, isolated patches, which are ecologically unstable.

- Climate Change: Altering temperature and rainfall patterns can push species beyond their physiological limits, disrupt synchronized life-cycle events (like flowering and pollination), and force species to shift their ranges, often with nowhere to go.

- Overexploitation: Illegal wildlife trade (poaching for bushmeat, ivory, and exotic pets) and unsustainable logging and fishing are decimating populations of key species.

- Invasive Alien Species: Non-native plants, animals, and diseases can outcompete, prey upon, or cause illness in native species that have no natural defenses against them.

- Pollution: Runoff from agriculture and industry can degrade freshwater and marine ecosystems within hotspots.

4. Conservation: The Path Forward

The designation of Biodiversity Hotspots is not just an academic exercise; it is a call to action. Conservation efforts in these regions are critical and multifaceted:

- Establishing and Managing Protected Areas: Creating national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and nature reserves is the cornerstone of hotspot conservation. However, it’s not enough to just draw boundaries; these areas require effective management and anti-poaching patrols.

- Working with Local Communities: Successful, long-term conservation must involve and benefit local and indigenous people. This includes creating sustainable livelihoods (e.g., ecotourism, non-timber forest products), supporting community-managed forests, and integrating traditional knowledge.

- Restoration Ecology: Actively restoring degraded lands by planting native trees and recreating habitats can help reverse some of the 70% loss and reconnect fragmented landscapes.

- Policy and Legislation: Advocating for strong environmental laws, land-use planning that prioritizes conservation, and international agreements (like the Convention on Biological Diversity) is essential.

- Scientific Research and Monitoring: Continuous research is needed to identify key species, understand ecosystem dynamics, and monitor the effectiveness of conservation interventions.

In conclusion, Biodiversity Hotspots represent the most critical and threatened reservoirs of life on our planet. They are irreplaceable and their fate is inextricably linked to our own. Focusing conservation efforts on these 36 regions is our most strategic and efficient hope for preserving the magnificent diversity of life on Earth for future generations.